Contributions

Abstract: PB2371

Type: Publication Only

Background

In 2016 Ferric maltol (Feraccru), was approved, as alternative to parenteral iron, as second line treatment for iron deficiency anaemia (IDA) in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) non responsive or intolerant to oral iron. Two clinical trials (AEGIS-1 & AEGIS-2), showed a statistically significant improvement in haemoglobin (Hb) with good tolerability.Both oral and parenteral iron are effective in correcting IDA, however parenteral iron is often used in IBD patients as oral iron is poorly tolerated. Parenteral iron is more expensive, and the cost of administration in a healthcare setting and nursing time required must also be considered.

Aims

We wanted to assess impact of the introduction of ferric maltol in our NHS Trust on the hospital budget and the nursing time.

Methods

We consider the following costs: 3 months of ferric maltol £168.78, iron infusion (drug plus appointment cost) £570.68. Nursing time for each infusion was estimated as 75 minutes.

First we analysed how many of our patients who were prescribed ferric maltol needed to switch to parenteral iron. For these patients we calculated the cost of both therapies as £739.46.We calculated how many parenteral iron infusions were administered to IBD patients in a period of 12 months before the introduction of ferric maltol. As last we calculated the potential savings, if ferric maltol prescription was extended to any patients with IDA.

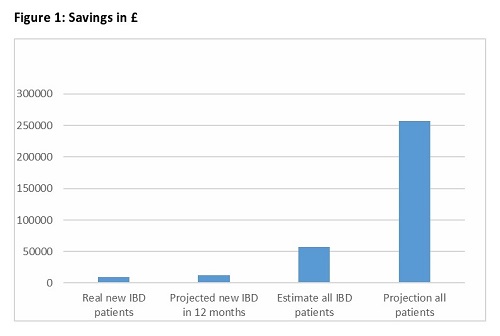

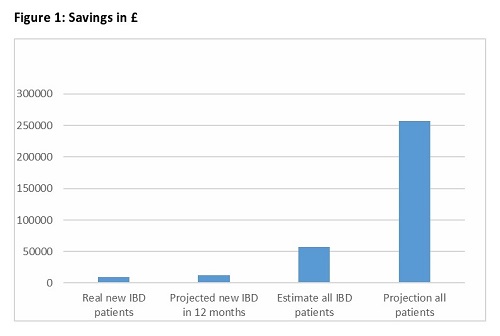

Results

In a period of 9 months we prescribed ferric maltol for 28 patients. If all the patients were treated with parenteral iron the total expense would have been £15960. As 4 (14%) of these had to stop the drug and have parenteral iron the cost have been calculated as £7005 with a saving of £8955 and 56% of cost reduction. In addition there was saving of 30 hours or 3.75 days in nursing time. If these savings were projected to a period of 12 months the calculation would be of £11940 and 5 days. In a period of 12 months IBD patients received 169 iron infusions at a total cost of £99.445. If all these patients were started on ferric maltol and only 14% of them needed parenteral iron the total cost would have been £42.220. The nursing time would decrease from 221 hours to 30 hours with a saving of 22.5 days. If we apply the same considerations to all the parenteral iron infusion, we estimated that in a 12 months period were issued around 800 parenteral iron prescriptions, the estimated saving with ferric maltol would have been £257.604 and 107.7 days.

Conclusion

Using Ferric maltol in our NHS Trust has been cost effective reducing costs and saving nursing time. Only new patients with IDA were prescribed ferric maltol, the patients who were already on IV iron maintenance continued with the parenteral therapy. The cost effectiveness will improve if we could switch to ferric maltol all the patients who were on parenteral iron maintenance and if ferric maltol was approved for treatment of any cause of iron deficiency. We recognise some limitation of this analysis. First the percentage of patients who had to stop the drug and needed parenteral iron could be underestimated because as patients prescribed ferric maltol towards the end of the study period had shorter follow up. Second, the number of appointments for iron infusion could have been overestimated as some of the patients could have been admitted. Last not all the patients, particularly those with active IBD could qualify for oral therapy and some could refuse it. Further data are needed to clarify these points and better estimate the real impact of this intervention.

Session topic: 36. Quality of life, palliative care, ethics and health economics

Keyword(s): Cost analysis, Cost effectiveness, Iron deficiency anemia

Abstract: PB2371

Type: Publication Only

Background

In 2016 Ferric maltol (Feraccru), was approved, as alternative to parenteral iron, as second line treatment for iron deficiency anaemia (IDA) in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) non responsive or intolerant to oral iron. Two clinical trials (AEGIS-1 & AEGIS-2), showed a statistically significant improvement in haemoglobin (Hb) with good tolerability.Both oral and parenteral iron are effective in correcting IDA, however parenteral iron is often used in IBD patients as oral iron is poorly tolerated. Parenteral iron is more expensive, and the cost of administration in a healthcare setting and nursing time required must also be considered.

Aims

We wanted to assess impact of the introduction of ferric maltol in our NHS Trust on the hospital budget and the nursing time.

Methods

We consider the following costs: 3 months of ferric maltol £168.78, iron infusion (drug plus appointment cost) £570.68. Nursing time for each infusion was estimated as 75 minutes.

First we analysed how many of our patients who were prescribed ferric maltol needed to switch to parenteral iron. For these patients we calculated the cost of both therapies as £739.46.We calculated how many parenteral iron infusions were administered to IBD patients in a period of 12 months before the introduction of ferric maltol. As last we calculated the potential savings, if ferric maltol prescription was extended to any patients with IDA.

Results

In a period of 9 months we prescribed ferric maltol for 28 patients. If all the patients were treated with parenteral iron the total expense would have been £15960. As 4 (14%) of these had to stop the drug and have parenteral iron the cost have been calculated as £7005 with a saving of £8955 and 56% of cost reduction. In addition there was saving of 30 hours or 3.75 days in nursing time. If these savings were projected to a period of 12 months the calculation would be of £11940 and 5 days. In a period of 12 months IBD patients received 169 iron infusions at a total cost of £99.445. If all these patients were started on ferric maltol and only 14% of them needed parenteral iron the total cost would have been £42.220. The nursing time would decrease from 221 hours to 30 hours with a saving of 22.5 days. If we apply the same considerations to all the parenteral iron infusion, we estimated that in a 12 months period were issued around 800 parenteral iron prescriptions, the estimated saving with ferric maltol would have been £257.604 and 107.7 days.

Conclusion

Using Ferric maltol in our NHS Trust has been cost effective reducing costs and saving nursing time. Only new patients with IDA were prescribed ferric maltol, the patients who were already on IV iron maintenance continued with the parenteral therapy. The cost effectiveness will improve if we could switch to ferric maltol all the patients who were on parenteral iron maintenance and if ferric maltol was approved for treatment of any cause of iron deficiency. We recognise some limitation of this analysis. First the percentage of patients who had to stop the drug and needed parenteral iron could be underestimated because as patients prescribed ferric maltol towards the end of the study period had shorter follow up. Second, the number of appointments for iron infusion could have been overestimated as some of the patients could have been admitted. Last not all the patients, particularly those with active IBD could qualify for oral therapy and some could refuse it. Further data are needed to clarify these points and better estimate the real impact of this intervention.

Session topic: 36. Quality of life, palliative care, ethics and health economics

Keyword(s): Cost analysis, Cost effectiveness, Iron deficiency anemia