REAL-LIFE FEASIBILITY OF AN IRON CHELATION PROGRAM WITH DEFERASIROX IN MYELODYSPLASIA AND OTHER ACQUIRED CHRONIC ANEMIAS: A SINGLE CENTRE EXPERIENCE

(Abstract release date: 05/18/17)

EHA Library. BERTANI G. 05/18/17; 182615; PB1901

Giambattista BERTANI

Contributions

Contributions

Abstract

Abstract: PB1901

Type: Publication Only

Background

Prolonged red blood cell (RBC) transfusion support in patients affected by myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and other chronic anemias may cause vital organs damage due to accumulation of non-transferrin-bound iron with consequent increased oxidative stress. Retrospective studies have shown that iron chelation may prevent aforementioned mechanisms and improve survival in low-risk MDS patients. Iron chelation is usually recommended in patients who received at least 20 RBC units and/or have a serum ferritin level of 1000 ng/ml or higher.

Deferasirox, an oral iron chelator, has widely replaced the use of deferioxamine, due to its greater manageability, especially in the elderly. However, an high dropout rate of approximately 50% of patients within one year was observed in the majority of clinical studies, the leading cause of discontinuation being gastrointestinal (G.I.) and renal toxicity and skin rash.

Aims

We aimed at evaluating the real-life feasibility of a program of prolonged iron chelation in a population of acquired chronic anemia patients. Thus, we performed a retrospective analysis to evaluate which is the percentage of patients who in our centre actually receive and tolerate deferasirox treatment, among the cohort of eligible patients.

Methods

Deferasirox treatment is considered at our centre in patients affected by MDS or other forms of chronic anemia (excluded chronic bleeding) who fullfill criteria for iron chelation (high transfusion burden, i.e. ≥ 20 RBC units and/or a serum ferritin ≥ 1000 ng/ml). Starting dose is usually 10 mg/kg, titrated up to 20-30 mg/kg as tolerated. The cohort of patients transfused at our centre during 2015 and 2016 was considered for analysis. Causes of unsuitability and of treatment discontinuation were extracted from our database.

Results

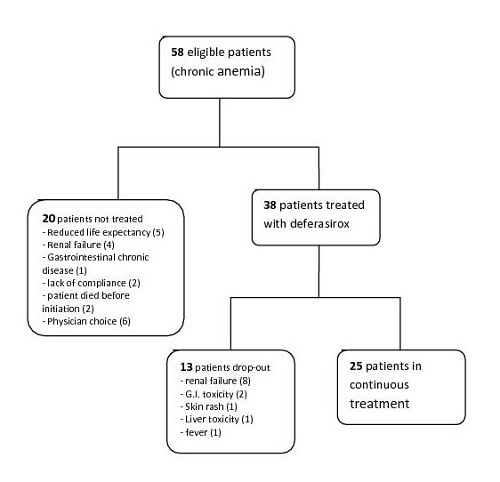

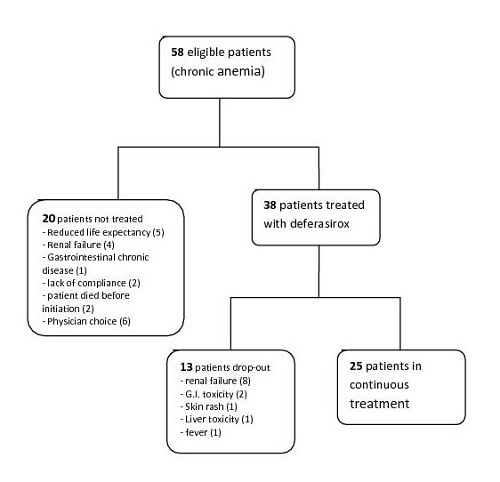

Our cohort consisted of 58 patients, mainly affected by MDS (45 pts); other diagnosis were myelofibrosis (6 pts), NHL (2) and multifactorial anemia, not related to blood cancer (7). Only 38 out of 58 potentially eligible patients were assigned to iron chelation (see the flow-chart). The leading cause of ineligibility in our cohort were a reduced life expectancy (5 pts), due to the hematologic disease itself or to comorbodities, and pre-exisiting renal failure (4). Importantly, in 6 cases patients were not offered iron chelation without a specific clinical reason: half of them (3/6) were non-MDS patients.

Furthermore, 13/38 patients had to interrupt the treatment, due to toxicity (mainly renal failure, followed by gastrointestinal toxicity, see flow-chart).

Overall, 25/58 (43%) potentially eligible patients, i.e. heavily transfused patients, initiate and continue an iron chelation program at our centre. The main cause for treatment discontinuation in our cohort was renal failure, while we had less difficulties in managing G.I. adverse events. Renal toxicity of deferasirox is known to be reversibile; however, in patients with pre-existing compromise and those who concurrently take nephrotoxic drugs, treatment may be difficult to carry on.

Conclusion

Our data are in line with literature. However, there is still room for improvement, especially in the category of non-MDS patients, who are often under-treated. Furthermore, the introduction of a new formulation of deferasirox, which is forthcoming, may hopefully reduce G.I. toxicity and improve tolerance and patients adherence to therapy.

Session topic: 28. Iron metabolism, deficiency and overload

Keyword(s): toxicity, iron chelation, Anemia

Abstract: PB1901

Type: Publication Only

Background

Prolonged red blood cell (RBC) transfusion support in patients affected by myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and other chronic anemias may cause vital organs damage due to accumulation of non-transferrin-bound iron with consequent increased oxidative stress. Retrospective studies have shown that iron chelation may prevent aforementioned mechanisms and improve survival in low-risk MDS patients. Iron chelation is usually recommended in patients who received at least 20 RBC units and/or have a serum ferritin level of 1000 ng/ml or higher.

Deferasirox, an oral iron chelator, has widely replaced the use of deferioxamine, due to its greater manageability, especially in the elderly. However, an high dropout rate of approximately 50% of patients within one year was observed in the majority of clinical studies, the leading cause of discontinuation being gastrointestinal (G.I.) and renal toxicity and skin rash.

Aims

We aimed at evaluating the real-life feasibility of a program of prolonged iron chelation in a population of acquired chronic anemia patients. Thus, we performed a retrospective analysis to evaluate which is the percentage of patients who in our centre actually receive and tolerate deferasirox treatment, among the cohort of eligible patients.

Methods

Deferasirox treatment is considered at our centre in patients affected by MDS or other forms of chronic anemia (excluded chronic bleeding) who fullfill criteria for iron chelation (high transfusion burden, i.e. ≥ 20 RBC units and/or a serum ferritin ≥ 1000 ng/ml). Starting dose is usually 10 mg/kg, titrated up to 20-30 mg/kg as tolerated. The cohort of patients transfused at our centre during 2015 and 2016 was considered for analysis. Causes of unsuitability and of treatment discontinuation were extracted from our database.

Results

Our cohort consisted of 58 patients, mainly affected by MDS (45 pts); other diagnosis were myelofibrosis (6 pts), NHL (2) and multifactorial anemia, not related to blood cancer (7). Only 38 out of 58 potentially eligible patients were assigned to iron chelation (see the flow-chart). The leading cause of ineligibility in our cohort were a reduced life expectancy (5 pts), due to the hematologic disease itself or to comorbodities, and pre-exisiting renal failure (4). Importantly, in 6 cases patients were not offered iron chelation without a specific clinical reason: half of them (3/6) were non-MDS patients.

Furthermore, 13/38 patients had to interrupt the treatment, due to toxicity (mainly renal failure, followed by gastrointestinal toxicity, see flow-chart).

Overall, 25/58 (43%) potentially eligible patients, i.e. heavily transfused patients, initiate and continue an iron chelation program at our centre. The main cause for treatment discontinuation in our cohort was renal failure, while we had less difficulties in managing G.I. adverse events. Renal toxicity of deferasirox is known to be reversibile; however, in patients with pre-existing compromise and those who concurrently take nephrotoxic drugs, treatment may be difficult to carry on.

Conclusion

Our data are in line with literature. However, there is still room for improvement, especially in the category of non-MDS patients, who are often under-treated. Furthermore, the introduction of a new formulation of deferasirox, which is forthcoming, may hopefully reduce G.I. toxicity and improve tolerance and patients adherence to therapy.

Session topic: 28. Iron metabolism, deficiency and overload

Keyword(s): toxicity, iron chelation, Anemia

{{ help_message }}

{{filter}}